The government’s advisory body on the Climate Change Act has issued a report showing that fracking could be made compatible with climate commitments so long as certain regulations are in place.

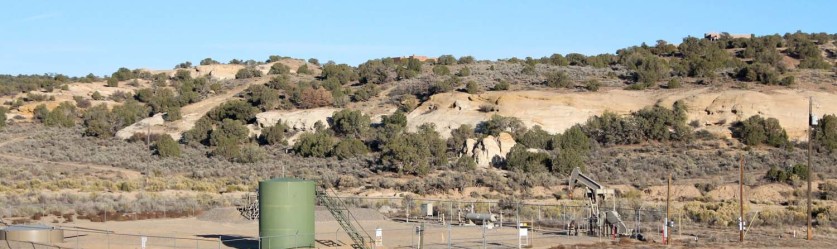

Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’ involves firing high pressured liquid into shale rock reserves in order to release natural gas. Currently, no fracking is taking place in the UK, but permission has been granted for exploratory work in certain areas.

Fracking has been the subject of intense debate recently, with several environmental campaigners arguing that issues ranging from contaminated water supply to increased pollution make it an inappropriate source of fuel production.

Recent plans to allow exploratory work in preparation for full-scale fracking in both Yorkshire and Lancashire led to repeated protests. Plans were blocked by the local council in Lancashire but were given the go ahead in Yorkshire, in a decision that some campaigners are currently seeking to overturn.

Despite campaigners protesting otherwise, the Committee on Climate Change has just published a delayed report (dated March 2016, but published on Thursday this week) that makes the case that, with certain increased regulation on the industry, fracking could be made viable and to not interfere with existing emission reduction targets.

The government has already given full support to fracking with David Cameron announcing back in 2014 that his government would be “going all out” on fracking, and Energy secretary Amber Rudd reinstating this support in more recent months.

The CCC’s report sets out three basic tests that would dictate the viability of shale gas extraction in terms of emissions regulation. If these tests are met, the CCC would back up the government’s support for fracking, albeit cautiously.

The report states: “Any assessment of the potential for shale gas exploitation in the UK is subject to considerable uncertainty. Not a single production well has yet been drilled. To inform our consideration, therefore, we have developed a number of scenarios for how production could develop and we have reviewed the international evidence for the emissions attached to production.

“In the light of that assessment, we have concluded that exploitation of shale gas on a significant scale would not be consistent with UK carbon budgets and the 2050 target unless three tests are met.”

The three tests cover separate areas – regulating overall emissions during production, regulating total use of gas so that overall consumption does not increase wildly as fracking takes place, and “the need to find additional abatement measures to compensate for the emissions attached to production, even under tight regulation”.

“If these conditions are met,” the report explains, “then shale gas could make a useful contribution to UK energy supplies, including providing some energy security benefits.”

In order to meet the first test – restricting emissions during production – certain regulations must be put in place stopping production in certain areas and taking action both to prevent gas leaks and swiftly address them if they do occur.

Passing the second will require balancing overall gas use, making sure that as domestic shale gas production increases, import levels reduce so that the total amount of gas consumption does not increase.

The third will involve working to cut polluting emissions in other sectors so that, as with gas consumption, the overall level does not increase.

The government have assured that these tests can all be passed, with a spokesperson from the Department for Energy and Climate Change saying: “We believe our strong regulatory regime and the government’s determination to meet our carbon budgets mean those tests can be and will be met.

“We have a very well developed but adaptive regulatory system which allows regulation to grow with the challenges it faces.”

However, the CCC are less certain, arguing that policy changes, or at least increased clarity, are likely to be required in order for the pursuit of fracking to remain consistent with legally established emissions targets.

One of the report’s authors, Imperial College London professor Jim Skea said: “We need stronger and clearer regulation. UK environmental policy allows quite a lot of discretion to the regulator and, depending on how things develop, it would be necessary to be more precise if you are to regulate emissions effectively.

“Existing uncertainties over the nature of the exploitable shale gas resource and the potential size of a UK industry make it impossible to know how difficult it will be to meet the tests.”

One recommendation from the CCC is that an independent regulatory body be created to govern the fracking industry, although the DECC has said that this is unlikely, explaining that “it is not in general an approach the government usually favours”.

Importantly, even if these tests are passed, it is unlikely that it will silence protesters concerned with issues beyond adherence to the targets set out in the Climate Change Act.

The CCC did make it clear in the report that they would only be investigating and reporting on the “compatibility of exploiting domestic onshore petroleum, including shale gas, with UK carbon budgets and the 2050 emissions reduction target under the Climate Change Act”. They do not investigate other issues cited by campaigners including noise, traffic and water pollution, which they say is outside of their scope.